When starting a research project, it is necessary to establish a project timeline in which all of the activities to be carried out are mapped out to keep on schedule. My question, one I know other women ask as well, is where and how to fit a pregnancy in the academic timeline?

During undergrad, we're too young and have the whole world ahead of us; during a masters', time is short, we have approximately two years in which it is impossible to think of things other than classes and the thesis. Then comes the doctorate. We're more mature, some are already married, but we still only think of research and publications – we know that after the four years of the doctorate we'll face the competition for jobs or need to be able to engage in a postdoctoral position. Therefore, the best option would be to wait for all of that to end, and decide to get pregnant after getting hired, with some professional, financial, and personal stability guaranteed. That stability generally occurs when a woman is around 37 years old, though, long after her fertility peak (Figure 1).

|

Figure 1. The age at which a scientist builds her career occurs at the same time of peak fertility

(measured by the number of ovarian follicles). Source: Willians & Ceci (2012).

|

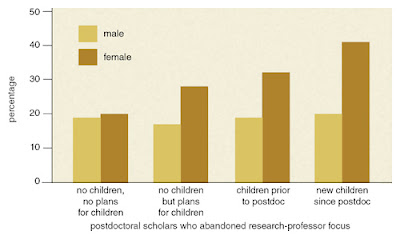

Although it is not difficult to name successful female researchers/professors with kids, the “graduate students that gave up their academic career after getting pregnant” scenario is far more common. As Figure 2 shows, the dropout percentage amongst post-doctorate researchers with no kids or plans to have kids is practically the same for both men and women. However, having a child after starting a post-doc doubles the dropout rate among women, but has no effect for men.

|

Figure 2. Influence of children and plans to have children in the postdoctoral

careers of men and women. Source: Williams & Ceci (2012).

|

Of course a child can alter a woman's life path, and also her academic productivity. Leslie (2007) shows that the more children a woman has, the less time she spends on professional activities (Figure 3). Shockingly (although the research dialog doesn't discuss reasons), the same study shows that the effect is reversed in men: more kids equals more working hours! I won't dare to go further in discussing causes for this difference, but I see two possibilities: a man sees it as more responsibility and, seeing himself as the family provider, works more (this is not necessarily his fault, the systemic tradition imposes and teaches women to take care of their home and men to provide for it); or they run from the domestic responsibilities for whatever reasons. A friend told me that when his child was a baby and required all mom's all attention and care, he would prefer to work late to avoid getting home before the baby was asleep, justifying himself by saying he was jealous of all the care his spouse had for the baby and felt he didn’t fit in his own home.

|

| Figure 3. The number of hours worked weekly for men and women compared to the number of dependent children. Source: Leslie (2007). |

One way to enhance female representation in universities and to reduce the academic dropouts is to focus on the problems mothers face to take care of a family while studying and researching. Williams and Ceci (2012) made a list of strategies that could be adopted to minimize problems and help families. As an example: universities could offer quality childcare, offer maternity leave for the primary care giver, regardless of sex; they could also instruct selection committees how to ignore curriculum gaps that happened while one was using more time to take care of the family (as an example, the committee would understand why someone didn't publish for some time if that time was used to take care of a newborn), and so on. What is not on the study's list, and what I consider extremely important, is a structural change in people's minds. I heard once that, to be accepted in a certain lab in Spain, the professor in charge would ask women to sign a form, agreeing not to get pregnant during the doctoral program. It's painfully hard to believe many minds still work like that!

And back to Brazil, where are we? USP, one of the largest universities in Brazil, has a childcare center that is praised by the parents, but just got at least 117 spots suspended for lack of funds invested in them (read more here). Not all funding agencies provide paid maternity leave for those with grants. Some progress can be seen, but many setbacks are still noticed. Even though some universities have adopted measures to help families' lives, a lot still need to be done.

I'll not be able to give an answer to the question I posed in the text's title here, mostly because I believe it's a personal decision and not just a cake recipe. Personally, I've been married for 3 years and will finish my PhD in the middle of 2016, with no intentions of expanding the family by then.

Nonetheless, I will not end the post with this matter. The blog will have testimonials of “women who are warriors,” that managed to study and have children; “altruistic women,” that gave up their academic career to dedicate themselves fully to their family and feel good about it; “scrappy women,” that stepped out of the university for a while to take care of kids and suffered many obstacles to get back in. My testimonial of an “indecisive woman” you already have.

What about you, have something to share? We welcome you to comment or contact us.

References

Goulden, M.; Frasch, K.; Mason, M. 2009. Staying competitive: Patching America’s leaky pipeline in the sciences. Center for American Progress,

Leslie, D.W. 2007. The reshaping of America’s academic workforce. Research Dialogue 87. https://www.tiaa-crefinstitute.org/public/pdf/institute/research/dialogue/87.pdf

Willians, W.M.; Ceci, S.J. 2012. When Scientists Choose Motherhood. American Scientist, Volume 100. http://www.americanscientist.org/issues/pub/when-scientists-choose-motherhood